Why Vulnerable Children Need Hope

By: Dr. Ashley Cross

“It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men” –Fredrick Douglas.

Have you ever met a hope-filled depressed person? Have you ever met someone full of shame and full of hope? No? Me neither. In fact, in a recent study I conducted on boys in foster care residing at Tulsa Boys’ Home, low-hope boys expressed feelings of self-doubt, abandonment, confusion, and low expectations while high-hope boys demonstrated positive thinking, managed aggression, respect and resilience.

When you think about foster children lacking hope, it is entirely understandable; we all know the statistics: Over 50% of foster alumni suffered mental health problems such as depression, social issues, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)(Northwest Study). Then, research has found a correlation between trauma and criminality (Martin & Stermac, 2010). Children in foster care struggle to form secure attachments and secure attachments develop earlier conscience development. Then on top of that, foster adolescents experience divided concentration between survival, persisting through the challenges of state custody and academics.

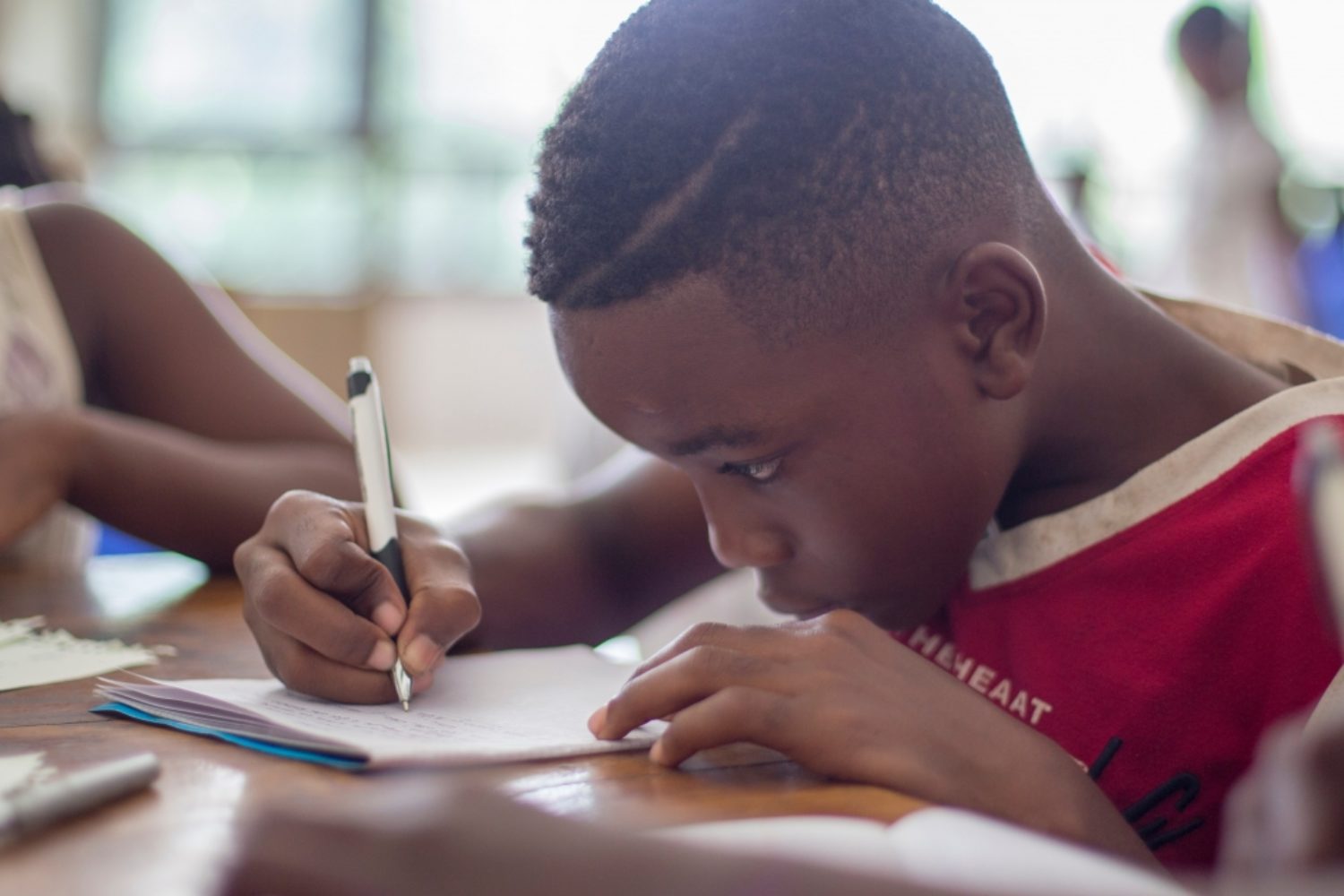

Research studies prove that adolescents in foster care have significant educational deficits and are behind their peers academically as they advance through school.

The impact of hope on academic performance is so substantial that researchers have determined that hope predicts a more considerable amount of variance in school grades than self-esteem. Researchers have committed an extensive amount of time to evaluate the relationship between hope and psychological health. Lower hope has been associated with more significant dysphoria, depression proneness, and maladjustment. Additionally, hope is predicting better life satisfaction, positive affect, and self-esteem, which helps individuals adjust to adversity. Hope is significantly correlated with positive attributional style and self-esteem, thus, making hope a crucial component to building resilience.

Hope should be the central focus of improving grades and lessening behavioral challenges. High-hope individuals, precisely high-pathways thinkers, are described as individuals capable of conceiving many strategies to accomplish a goal and plan for alternatives when they are confronted with challenges, goal blocks, and perceived failures.

Being trauma-informed only addresses one component of working with vulnerable families and children; however, Snyder’s hope theory provides an approach to build on a trauma-informed methodology. Snyder’s hope theory proposes that levels of hope can change over time through persistent intermediations, such as counseling and education; therefore, they can be applied to create ways to foster hope and resilience.

Recently, researchers at the University of Oklahoma Center for Hope Research have studied the theory of hope on vulnerable populations and concluded that high-hope individuals have higher life satisfaction, higher positive affect, better affect balance, higher self-esteem, and higher relationship quality. Isn’t that what we want for the children we work with and serve?

Hope is a substantial component that influences an individual’s self-esteem, life satisfaction, resilience, overall achievement, including academic achievement, and overall health. Furthermore, hope, in contrast to toxic stress, essentially can heal the brain.

Children in foster care have several odds stacked against them, and they need caring adults to give them hope, help them build their hope, and sustain their hope. Parents are drivers of hope, and when situations occur that require children to be removed from their parents, they are removed from their primary hope givers.

But there is hope! It begins with YOU. Regardless of what role you play in the life of a foster child or other vulnerable children, you are serving as a source of hope. YOU are now their hope giver. There is no way your child will thrive, and there is no way their lives will turn around without hope.

Let’s begin building their hope. Wait, but first, we have to make sure you have hope. You cannot give something you do not have.

Take these simple steps in the right direction towards hope:

- If you have not already, take the Adult Hope Scale at https://hopescore.com/hope-score/. Begin tracking your hope regularly.

- Love on yourself. Take the Love Language test https://www.5lovelanguages.com/ and do something that demonstrates your love for yourself.

- Take time to focus and journal on your child’s strengths. Ask yourself these questions:

- What strengths does my child have?

- When are they happiest?

- What are my hopes and aspirations for them?

My next article will teach you how to help your child “fail” well.

You can download this article here: Why Vulnerable Children Need Hope

References:

Arnau, R. C., Rosen, D. H., Finch, J. F., Rhudy, J. L., & Fortunato, V. J. (2007). Longitudinal effects of hope on depression and anxiety: A latent variable analysis. Journal of personality, 75(1), 43-64.

Bailey, T. C., Eng, W., Frisch, M. B., & Snyder, C. R. (2007). Hope and optimism as related to life satisfaction. Journal of Positive Psychology, 2, 168-175.

Ciarrochi, J. W., Heaven, P., & Davies, F. (2007). The impact of hope, self-esteem, and attributional style on adolescents’ school grades and emotional well-being: A longitudinal study. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 1161-1178.

Dubriwny, N., & Hellman, C. M. (2010). The impact of program service on the parent-child interaction and hope. Retrieved from the Parent-Child Center website: http://www.parentchildcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/PCCT-Report.pdf

Heaven, P., & Ciarrochi, J. (2008). Parental styles, gender, and the development of hope and self‐esteem. European Journal of Personality, 22(8), 707-724.

Martin, K., & Stermac, L. (2010). Measuring hope: Is hope related to criminal behavior in offenders? International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 54(5), 693-705.

O’Higgins, A., Sebba, J., & Gardner, F. (2017). What are the factors associated with educational achievement for children in kinship or foster care: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 79, 198-220.

Rossen, E., & Cowan, K. (2013). The role of schools in supporting traumatized students. Principal’s Research Review, 8(6), 1-8.

Shorey, H. S., Snyder, C. R., Yang, X., & Lewin, M. R. (2005). The role of hope as a mediator in recollected parenting, adult attachment, and mental health. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 22, 685-715.

Snyder, C. R., Shorey, H. S., Cheavens, J., Pulvers, K. M., Adams, V. H., & Wiklund, C. (2002). Hope and academic success in college. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(4), 820-826.

Valle, M. F., Huebner, E. S., & Suldo, S. M. (2006). An analysis of hope as a psychological strength. Journal of School Psychology, 44(5), 393-406.